#hittite cuneiform

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Classicstober Day 14: Helen (𐀁𐀩𐀛/𒄭𒇷𒉌)

Helen of Troy… Helen Queen of Sparta… Helen Princess of Sparta… Helen the daughter of Leda and Zeus… the face that launched a thousand ships wore many masks over the course of her life but one thing that remains the same is how compelling she remains as a character. Many thanks to @symeona for helping me with her look!

Helen is a character intrinsically associated with her appearance, but early sources do not describe her at all outside of demonstrations of her status. For this piece, I have borrowed from two sources. The first is symeona, who's excellent translations on Ancient Greek color theory informed my take on Achilles. The second was that wretched and accursed fnckboy Ovid, who described Helen's mother Leda as having 'snowy white' skin and black hair. Since Zeus appeared to Leda in the form of a swan, and considering how pale Leda was, I decided to make her somewhat swan-like in appearance, with big black eyes and naturally ruddy lips to seal the deal.

First, let's talk about Helen the Spartan (rendered here in Linear B as 'Eleni of Laconia'). Despite mainly being known for her role in the Trojan War, Helen lived the majority of her life in Sparta and her husband Menelaus claimed the throne of Sparta through her. Laconia and Sparta are some of the oldest sites of Mycenaean culture, so Helen got to be depicted as Mycenaean as all getout. The high-piled hair, the diadem, the open tunic, and the bracelet are all very common in depictions of Mycenaean and Minoan women. She also has very elaborate florets to mark her status. The red fabric and large gemstones mark her wealth too i completely forgot to draw in the necklace she wore in the sketch version.

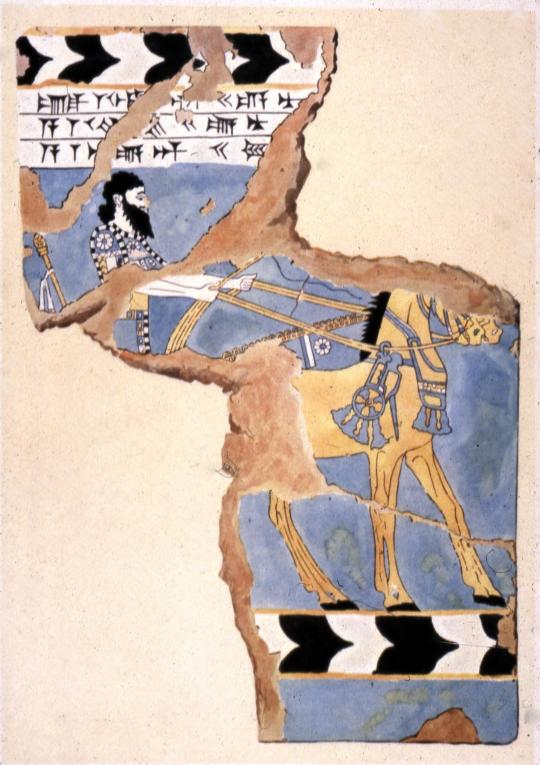

I mentioned before in my picture of Cassandra and Hector that I am basing the Trojan looks heavily on ancient Hittite clothing, and this is no exception. I know the movie Troy sucks for lots of reasons, but I did like that they made the Trojan theme color this very rich blue so I decided to add that here; dark, rich colors in general are very expensive to produce, so even if it's not red the saturation makes the cloth very expensive and a mark of royalty. I based her clothing and jewelry off a Hittite statue, but I decided to omit the tall hats that Hittite women appear to wear under their veils; I kind of wanted that to represent status, so only Andromache and Hecuba would wear the tall hats if I depict them.

I was not trying to make a commentary with it, but it does strike me how conservative the veiled, tunic wearing Hittite woman looks compared to the open-bodiced Mycenaean woman. That could easily be read into, but I'm just going to leave it as depiction and not try to ascribe any symbolism to it.

The decorative circle around Helen represents several things. Horses feature prominently in her life. The Trojan Horse is the most well known, but the wedding oath that Tyndareus made Helen's suitors swear to was sealed with the sacrifice of a horse too. Anemones are a sacred flower to Aphrodite (long story) and the white lilies seem like a fun way to evoke the 'pure woman' image.

Also in the circle are depictions of Eris' golden Apple of Discord. For the life of me, I could not find any translation related to fairness or beauty in any Mycenaean dictionaries so I had to cheat: "𐀴 𐀏𐀪𐀯𐀳𐀂/ti ka-ri-se-te-i" is just a phonetic transliteration of ΤΗΙ ΚΑΛΛΙΣΤΗΙ (tē(i) kallistē(i)), translated as 'for the fairest.'

#classicstober#classicstober2023#classicstober23#helen of troy#helen of sparta#greek mythology#ancient greek mythology#tagamemnon#linear b#mycenaean#hittite#hittite cuneiform#cuneiform

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

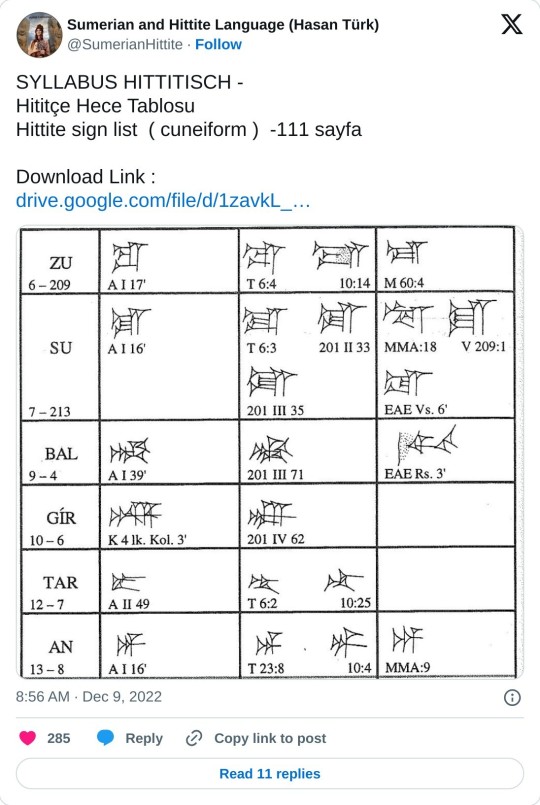

Download Link : https://drive.google.com/file/d/1zavkL_xhvVc2dnPOjCThxy3dmMjfUD_y/view?usp=sharing

#Sumerian#Hittite#Language#Hasan Türk#Hittite cuneiform#ancient#Hittite Syllable Table#Hittite Syllable#Sumerianlanguage#Sumerianwriting#Sumeriacuneiform#ancientsumer#ancientsumerans#Babylon#Babylonia#ancientiraq#iraq#cuneiform#Assyriology#العراق#العراقـالعظيم#سومر#السومريين

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

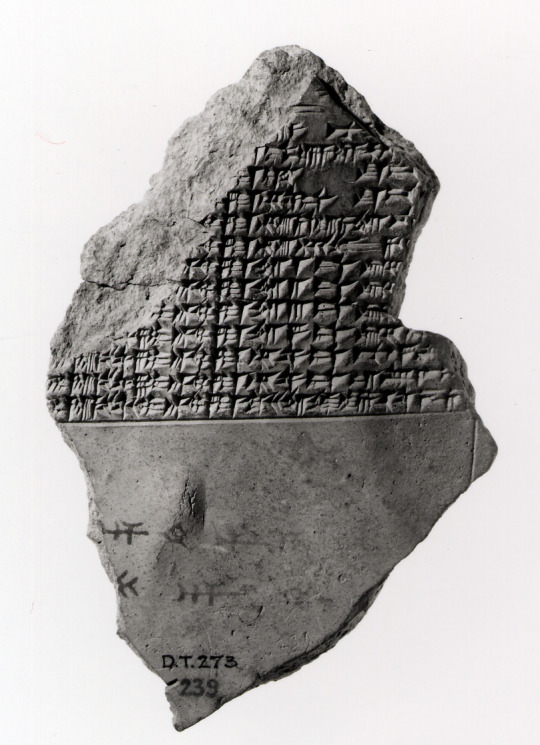

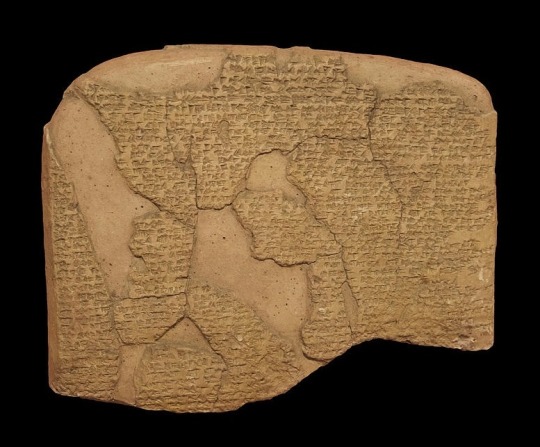

A Hittite cuneiform tablet declaring the first surviving recorded peace treaty in history between Ramesses II and Ḫattušili III respectivly rulers of the New Kingdom of Egypt and the empire of the Hittites. The tablet is written in the Hittite language and their cuneiform.

This is one of three known relics of the treaty. Also known as The Treaty of Kadesh.

Circa 1259 BC

The tabelt is displayed at the Museum of the Ancient Orient in Turkey

#egyptology#ancient civilizations#ancient world#antiquity#archeology#ancient history#egyptian history#ancient egypt#hittite empire#hittite#archaeology#artifacts#cuneiform#anatolia#mesopotamia#artifact#ancient artifacts

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, by imperial archive, they mean mostly the building that housed the documents. There seem to be a few documents in fragments, but more seals than documents. I think. It's a bit confusing.

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drawing Cuneiform, Part 3/3

(Previous)

So, how can we draw these signs in a way that's clear and legible, without getting too overcrowded and busy?

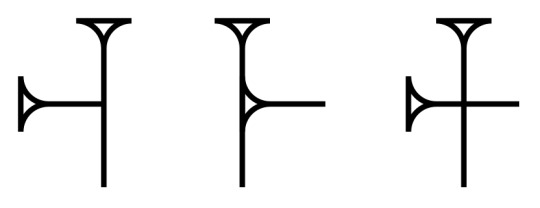

We have to make it clear where strokes start and end, because these three are all different signs (the sounds qa, me, and bar). This means we can't only mark the heads.

And we have to be able to mark multiple heads on a single stroke, because these two are different signs (the number 2, and the sound a). This means we can't only mark the tails.

So how can we achieve both of those goals, without ending up with a mess of heads and tails everywhere?

Well, it turns out some ancient scribes tried to solve the same problem!

Ashurbanipal, the last of the "great" kings of the Assyrian Empire, was known for being a horrifically cruel and bloodthirsty ruler (which is part of why he was the last of them). But he was also a great scholar, and he devoted a lot of his time and effort to building the Royal Library, which was meant to include all the knowledge of the world. It's thanks to this Royal Library that we have as much ancient Mesopotamian literature as we do today!

Like any good librarian, he made sure that every tablet filed in the Royal Library was properly labelled, and like any good emperor, he made sure they all had his own name on them, just in case. Usually this was stamped into the clay the normal way. But sometimes the tablets brought back from sacking a city had already been fired. What then?

Well, in exactly three specific cases, we've found this library information (the "colophon") written on in ink.

Here are zoomed-in images of the two I was able to find in the British Museum's collection. The third should be somewhere in there as well, but I haven't been able to locate it.

The text is pretty badly faded, but we know what it says based on other tablets from the Library: "Palace of Ashurbanipal, King of the World, King of Assyria".

Now this looks promising! This isn't just the improvised work of a scribe whose tablet dried too fast—according to Irving Finkel, the British Museum's cuneiform expert, the neatness and elegance of the writing suggests that there was a long tradition of this. Ink is just less durable than fired ceramic, and less likely to survive for the thousands of years it took us to rediscover these artifacts.

It's hard to extrapolate much from just these two inscriptions, but we can say a few things:

The heads are drawn with curved lines, and the tails with straight lines

Multiple tails can share one head, and multiple heads can share one tail

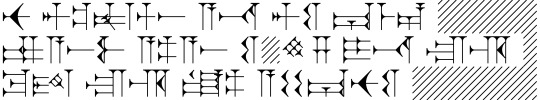

So let's see if we can render some text in this style! Here's what the full colophon should look like, if the rest of the text had survived:

I had to make a few guesses to make this work. We don't have any "Winkelhaken" strokes in the surviving text—the ones that look like big hooks, without a head or tail—so I just guessed at how they would be drawn.

But still, I think we've found our winner. This is the most readable style I've seen yet for writing cuneiform in two dimensions. You can see clearly where all the heads and tails are, you can tell the heads apart from the tails, and each wedge takes a maximum of two pen strokes to draw, a big improvement over our earlier versions!

So to finish off, here's how our Gilgamesh excerpt would look in this style:

Very readable, I think!

Next up: how exactly does this style work?

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

500 Hittite cuneiform tablets were translated at the start of the project by photographing them in high resolution and scanning them with 3D technology. According to the results of the testing, the AI’s success rate was 75.66%.

Project coordinator Gavaz also explained that they tried to decipher the Hittite language manually, but this method proceeds more slowly and is prone to errors, while AI works in a shorter time and with a low margin of error.

The fact that some tablets are broken or deformed and other factors have an effect on the results. But we are trying to solve high-resolution photos with different algorithms.

The data obtained from the deciphered tablets will be shared with the scientific world by Hittitologists. Also, the public will be able to view the cuneiform clay tablets once the translation phase is finished in the soon-to-be-opened Hittite Digital Library.

#ancient#history#archeology#ai#cuneiform#clay tablets#hittites#scanning#ancient languages#translation

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

30'000 cuneiform tablets were unearthed in the ancient city of Hattusha, capital of the ancient Hittite empire, in Turkey revealing an entirely new language.

⛰⛰⛰

#anime#ufos#aliens#scifi#extraterrestrials#animation#ancient aliens#comic books#fantasy#manga#turkey#hittite#cuneiform#language

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

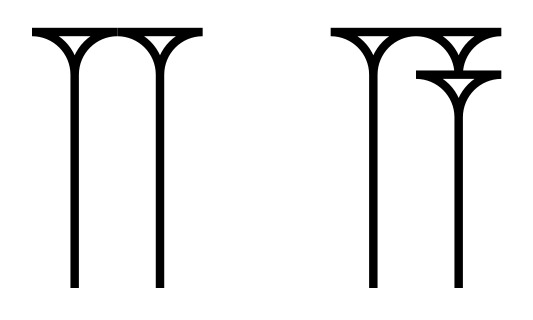

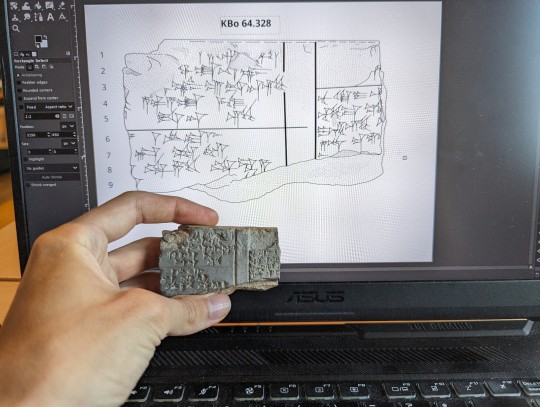

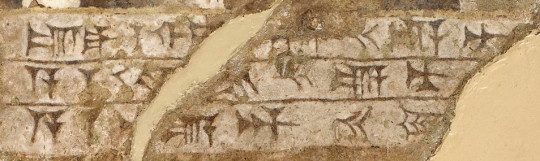

speaking of the summer school, i got to handle actual tablet fragments (!) and made a hand copy of this one

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

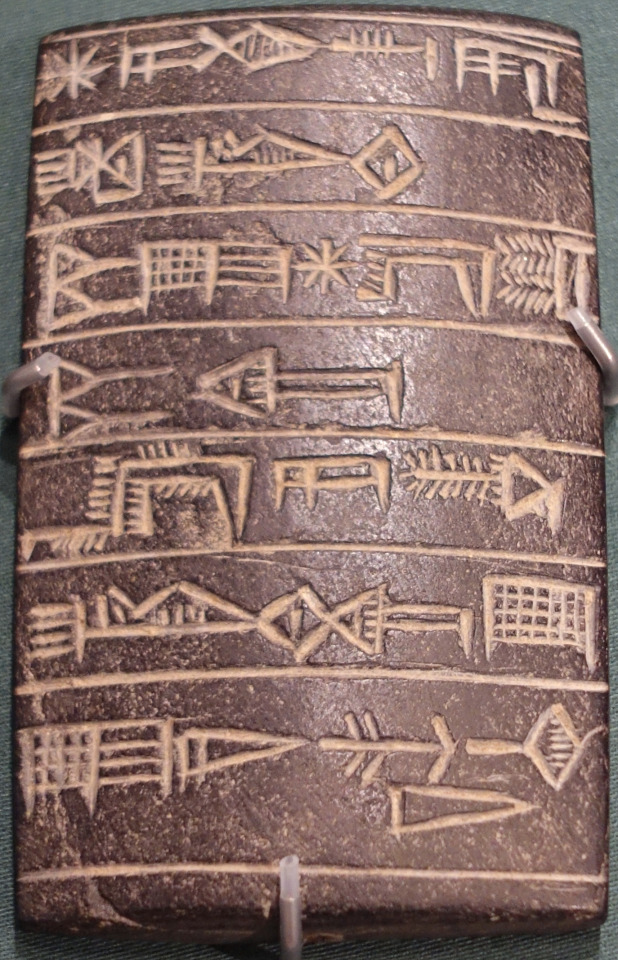

Treaty of Kadesh

The Kadesh Treaty (Hittite version), early cuneiform inscription discovered at Boğazköy, Türkiye. The world’s earliest peace treaty that is still extant between the Hittites and Egyptians. It was signed by Hattušiliš III and Ramesses II in 1259 BC.

The battle of Kadesh is one of the world’s largest chariot battles, fought beside the Orontes River, King Ramesses II sought to wrest Syria from the Hittites and recapture the Hittite-held city of Kadesh. There was a day of carnage as some 5,000 chariots charged into the fray, but no outright victor.

Now in the Istanbul Archaeology Museums.

Read more

88 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! This is probably a long shot, but I'll try my luck. I need to know how to say "yes" in Hittite to settle a bet with a friend. Either a transliteration or cuneiform would do. Can you help or do you know of any resources or other people who can? Thanks!

the resources i was able to search don't seem to have an entry, and i don't know enough about hittite to be able to reframe that search to something more appropriate if there isn't a straightforward equivalent...

(i tried the chicago hittite dictionary and ut austin's hittite online)

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seal of Tarkasnawa, King of Mira

Hittite, Anatolia, late 13th century BCE (Hittite Empire)

Luwian hieroglyphs surround a figure in royal dress. The inscription, repeated in cuneiform around the rim, gives the seal owner's name: Tarkasnawa, king of Mira. The name of the ruler was previously transliterated into English as Tarkondemos and Tarkummuwa. Other inscriptions naming Tarkasnawa of Mira are known, including seals found at Hattusa (the capital of the Hittite Empire) and the Karabel rock relief carving near Izmir, Turkey. Located in west-central Anatolia, Mira was a vassal state of the Hittite Empire. This seal, originally published in the 1860s, was purchased in Izmir by its first known modern owner, A. Jovanoff. Its famous bilingual inscription provided the first clues for deciphering Luwian hieroglyphs, which were previously called Hittite hieroglyphs.

241 notes

·

View notes

Note

This is incredible! Thanks for showing these extremely useful cuneiform tools (and for building one!)

Hi! I’ve been trying to find a good cuneiform version of the Epic of Gilgamesh and have been completely unsuccessful (mostly because I’m not interested in buying one, just finding one online or at the library). Regardless, all I’m trying to find is the cuneiform for a couple of lines early in Tablet 1: in Mitchell’s English version, “Take out the tablet of lapis lazuli. Read/how Gilgamesh suffered and accomplished all.” (p.70) I was wondering if you could help me out with this in any possible?

Hello! I don't have the cuneiform but can maybe help you on your way. These lines are ll. 26-28 of tablet I in the Standard Babylonian version. George translates them as "[Open] the lid of its secret, [lift] up the tablet of lapis lazuli and read out / all the misfortunes, all that Gilgamesh went through!" Helle (2021) opts for "Open the door to its secrets, / take up the tablet of lapis lazuli and read aloud: / read of all that Gilgamesh went through, / read of all his suffering."

The Akkadian for this is

[pi-te-m]a bāba(ka2) ša2 ni-ṣir-ti-šu2 [i-š]i ma ṭup-pi {na4}-uqnî(za-gin) ši-tas-si [mim-m]u-u2 {dingir}-Giš-gim2-maš ittallaku(du-du)-{ku} ka-lu mar-ṣa-a-ti

The portions not in italics in (parenthesis) are the sign form of the prior word, while those in {brackets} are written determiners; neither are spoken aloud. [Square brackets] are fragmentary and are assumed. This means the pronunciation would be Pitema bāba ša niṣirtišu / Iši ma ṭuppi uqnî šitassi / Mimmu Gišgimmaš ittallaku kalu marṣāti (or something close to it, my Akkadian isn't great so forgive any errors!)

Unfortunately there's no actual cuneiform copy of the tablet I can find online, but if an Akkadianist reading this can help with the exact signs I'm sure the asker would appreciate it!

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

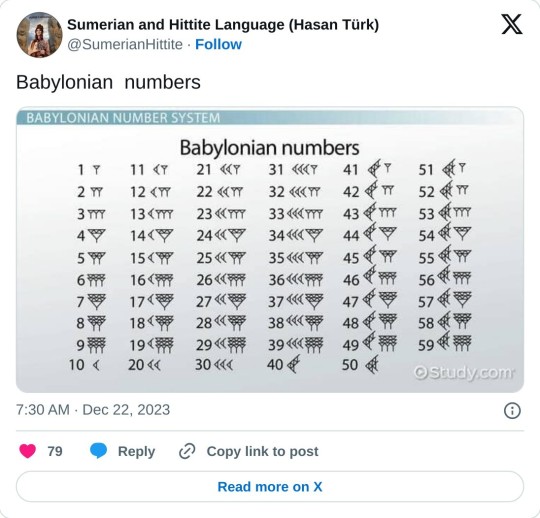

The Babylonians used a base 60, or sexagecimal, number system which is preserved in tablets made by pressing into the soft clay styli with carved cuneiform script. Our habit of giving 360o to a circle, 60 seconds in a minute and 60 minutes in an hour are cultural artifacts passed down to us from the Babylonians.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

An excavation in Turkey has brought to light an unknown Indo-European language. Professor Daniel Schwemer, an expert for the ancient Near East, is involved in investigating the discovery. The new language was discovered in the UNESCO World Heritage Site Boğazköy-Hattusha in north-central Turkey. This was once the capital of the Hittite Empire, one of the great powers of Western Asia during the Late Bronze Age (1650 to 1200 BC). Excavations in Boğazköy-Hattusha have been going on for more than 100 years under the direction of the German Archaeological Institute. The site has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1986; almost 30,000 clay tablets with cuneiform writing have been found there so far. These tablets, which were included in the UNESCO World Documentary Heritage in 2001, provide rich information about the history, society, economy and religious traditions of the Hittites and their neighbors.

Continue Reading.

354 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nice that for once it isn't an economic document. Not so nice that it's about a catastrophe.

192 notes

·

View notes

Text

Drawing Cuneiform, Part 2/3

(Previous)

For the most part, ancient scribes didn't really draw cuneiform. They wrote it by pressing the stylus into the clay. That's what the system was designed for, after all!

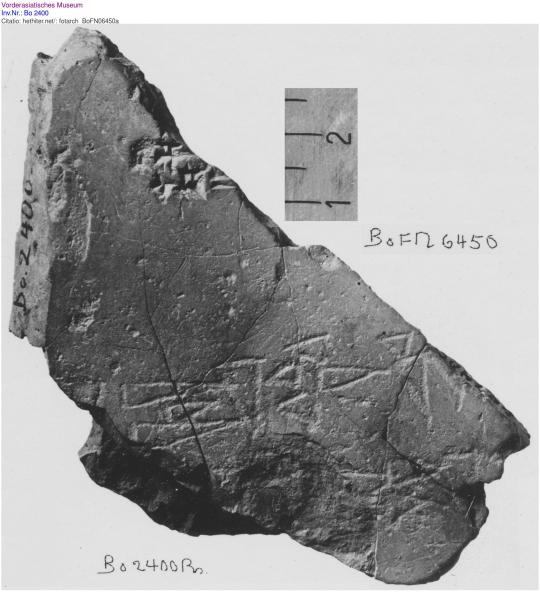

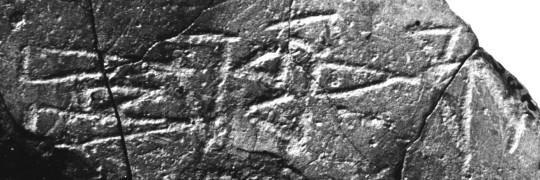

But occasionally that wasn't possible. For example, what if you wrote out a whole tablet, but it dried before you could sign your name on it? Well, you might have to find a sharp implement and just scratch it into the clay, like with this Hittite tablet (known as Bo 2400 for this fragment or KBo 3.9 for the whole thing).

Here's a zoomed and enhanced version:

(The original publication of this tablet claimed the scribe's name was written in ink with a reed pen, but from the photos, it very much seems to be inscribed. These three signs say -ma-wa-za- or -ku-wa-za-, but I don't know if that corresponds with the full name of any scribe we know about.)

This style seems straightforward enough. Just draw the outline of the triangles! And this is how some modern cuneiform fonts do it, so that seems like another good option.

Here's how that Gilgamesh excerpt from last time would look in this style.

Hmm…less busy, but also it's hard to tell where exactly the strokes meet when their points are so thin.

But this unfortunate Hittite scribe isn't the only one who needed to draw out cuneiform on a flat surface. Here's a wall tile from the British Museum, from the reign of the Neo-Assyrian ruler Tukulti-Ninurta II.

And zoomed in a bit:

(Images from the British Museum, CC-BY-NC-SA.)

This looks pretty close to our autograph style from before, just with the heads filled in! Let's try this.

Pretty! But the stroke heads still stand out quite a lot. That seems to be the biggest problem we're facing in trying to make the 2D cuneiform drawings look good: it's very important to show where the stroke heads are, but it always takes so much ink and makes the whole thing look more complicated than it should.

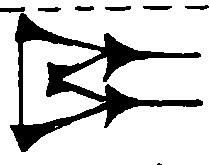

Another option uses a flat triangle for the head, like—ALLEGEDLY—on this stone tablet from the Sumerian king Il of Umma.

See those big strokes on the left with the triangular heads? Those are often used as an example of the "triangle-head" style…but something's wrong here. Why don't any of the other strokes have heads like that?

Well, it's because those aren't actually the stroke heads! That's the sign DUMU, meaning "son", and this is how it looks on clay (around this era, from Labat's Manuel d'Epigraphie Akkadienne):

So those aren't the stroke heads, those are just extra strokes!

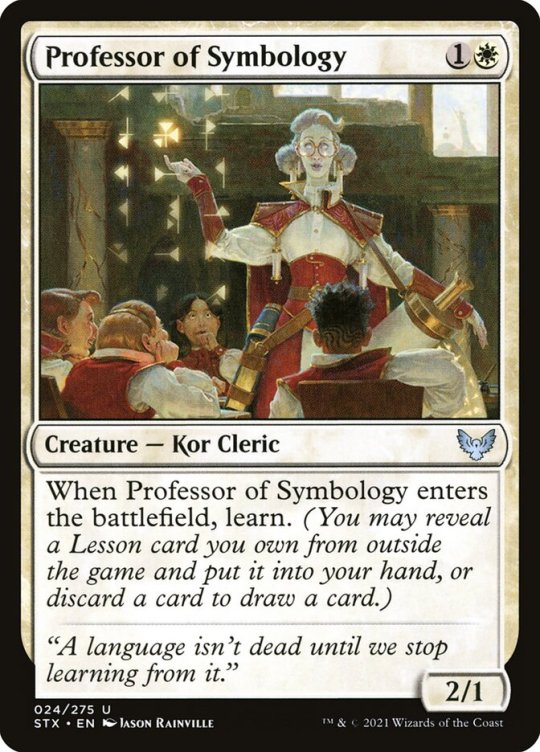

I implemented the triangle head style anyway, though, for a much less lofty reason. While I was working on this project, a Magic the Gathering card came out with fantasy cuneiform on it:

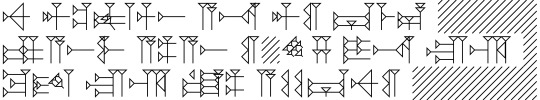

And I wanted to make a version of this card in Hittite as a joke, imitating the style that these glyphs are drawn in. So here's how the Gilgamesh text would look in the "triangle head" renderer.

It has a certain aesthetic appeal, but it's a bit too blocky for my liking. (There's also a version that fills in the triangles, but that's even blockier.)

But there's one other form of ancient "drawn" cuneiform that I was introduced to a couple months ago, that I think will solve all these problems.

(Next)

6 notes

·

View notes